Kid A, Rez Infinite, and the Yin and Yang of Y2K

My favourite game of all time is Rez Infinite. My favourite album of all time is Radiohead’s Kid A.

Different mediums, but two sides of the same coin. A yin and yang approach to the same concept: technology, futurism, and our place, as humans, alongside the developing world wide web.

Tetsuya Mizuguchi’s Rez, whether in its vanilla Dreamcast release or its modern Infinite incarnation, looks at a hypothetical future of digital unpleasantness, but drills down to its squidgy, human core with a laser focussed beam of optimism. Eden, the omniscient AI at the heart of Rez’s story, experiences an existential crisis, with the player character then having to infiltrate its firewalls to reboot the AI to help it understand its place in the world. The ending may be ambiguous, but the experience itself, from stage one through to stage five, is one of development and expansion, endeavour and connection.

As Eden is cleansed and rediscovers their value and import within this now digital world, the player comes away feeling a sort of euphoria. The player has saved the day as in countless games before, but in doing so, will likely have confronted, via this hour of sensory overload, their own place within a newly digital space.

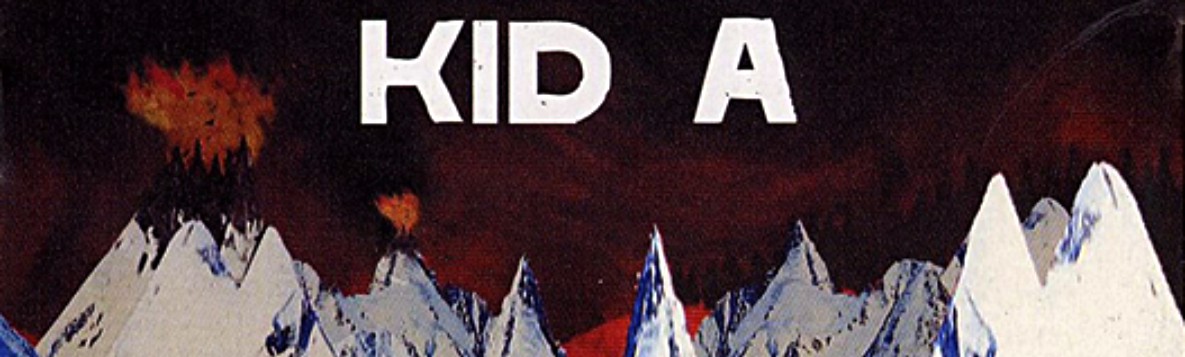

Radiohead’s Kid A, the wildly experimental follow up to critical darling OK Computer, concerns itself both sonically and thematically with a similar focus: humans’ place within a changing technological world. But far from the bright crescendo of Rez and Eden’s reboot and redemption, Kid A looks at the contagion of the web through a distorted glass-half-empty lens.

Lyrically, the band open with the feart realisation that modern man seems to sit atop a pile of both everything and nothing in Everything in its Right Place; paint grim pictures of a digital Pied Piper leading the innocent from the safety of a hypothetical town in the title track; and detail the coalescence of a media’s collective scaremongering clashing with an equally panicked reality on Idioteque.

But it’s aurally that Kid A’s almost symbiotic but contrasting relationship with Rez really plays out.

Rez is a game of such intoxicating power, I want to stick it on every time I glance at a screenshot.

Both are pieces of media heavily influenced by techno, but both use a similar starting point to again split onto their own divergent paths. Take the skittering beats common to both Rez’s soundtrack and the backing of Idioteque for example. They act as the building blocks for a song’s swell and development in the Dreamcast favourite, but as a deliberate, chilly repeat in Radiohead’s work that suggests a relentlessness to our digital society’s constant churn.

Whereas the trance-like state electronic dance music can trigger is used in Rez as an attempt to envelop the player and guide them through their journey with the love and light of each track’s peaks and troughs, Radiohead latch onto the thin, crystalline timbre of EDM to contrast the perceived analogue warmth of guitars or live drums in a battle of traditionalism versus digital revolution.

Rez and Kid A. Hope against hopelessness.

Stanley Donwood’s artwork for Kid A is some of the very, very best around.

The release of these two pieces of disparate but alike media are separated by roughly a calendar year, though given the length of development cited for both projects it’s not inconceivable to think they may have shared some cultural inspiration.

Indeed, both have been open about the aforementioned link to dance music, and both parties, in interview, have also made reference to a more primal jazz influence in each work. Radiohead cite Charles Mingus and his contemporaries as inspiration for the dissonant brass work in songs like The National Anthem, and Miziguchi often links the push for synaesthesia in his output to the paintings of Wassily Kandinsky, a practitioner who attempted to reinterpret the rhythms and modes of jazz through visual art.

But it’s the looming, pervasive threat of Y2K as a numerical millennial marker and cultural touch point that seems to work its way into both game and album alike; the societal realisation that technology, something increasingly intertwined with every other aspect of our lives, had such far reaching, chaotic power for both good and bad.

Although largely unfounded, the ever-present 1999 fear of sum-zero digital reset that led to individuals stockpiling tinned food and ammunition in particularly extreme cases, is present in both Rez’s story of a society marked by humanity’s failure to act as stewards for nature as they loved thy neighbour, and Kid A’s worried, fingers-in-ears insularity as evidenced on How to Disappear Completely in lines like “I’m not here, this isn’t happening”.

It’s all about how we choose to frame challenge and change. Technology revolves as technology evolves. At the heart of every mechanical, binary ones-and-zeros robot choice is humanity. The laser cut rocks are doing maths because we had the intelligence and creativity and wherewithal to see if they could. That’s the core difference between Rez and Kid A: at its heart, Rez remembers what powers these totems of human development, whilst Kid A looks on anxiously with messaging that suggests the protagonists of its songs have made a snap Skynet hypothesis and judgement.

There is value in both responses, but as with almost everything, it feels like the real answer is somewhere in combination or convergent run off. Technology is a murky grey. There are variables and unknowns that paint simple pessimism or optimism towards the digital revolution relatively futile even 20+ years after these two landmark releases.

Embrace both. Play Rez. Listen to Kid A.