Jackass: The Game and Licensed Mediocrity

2007’s Jackass: The Game is a bad game. More importantly, it’s also a bad Jackass game.

Tie-ins are a curious thing. With the classic collectathon tie-in most prevalent in the nineties and noughties now mostly a thing of a past outside of the single publisher Outright Games holding the torch valiantly, most franchises either align with grubby free to play mobile titles or don’t bother at all.

The PS2 though was a hotbed for games based on films; games based on TV; games based on books; or even games based on adverts for ringtones.

In the mid-2000s,Jackass as a franchise was perhaps at its most culturally virulent. The MTV series may have ended several years prior, but 2006’s Jackass 2 had done gangbusters at the cinema, several spin-offs like Wildboyz were pulling in big television audiences, and the Tony Hawk’s series had been realigned, perhaps damaged permanently, by Neversoft’s pivot to full on Bam Margera-dumbo-stunt-action in Underground 2.

Queue the licensed tie-in. Jackass: The Game placed players in the seat of series director Jeff Tremaine, commanding the series reality stars through increasingly stupid stunts that could be recorded, edited and then packaged to ostensibly create a new series of the show for MTV.

In concept, it’s reasonably solid. In execution it manages to totally miss the point of Jackass as a cultural phenomenon.

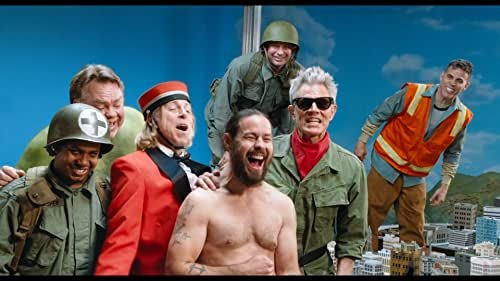

Please go and see Jackass Forever in the cinema.

Jackass Forever is a stupid film. Ten years after the gang’s last cinema outing, it could have limped to the big screen, attempting to ride its own coattails to mediocre box office success and a few gross out giggles. And yet, everything about it just works. Every concern voiced prior to its delayed release - worries about the expanded cast, a feeling that the format may feel like a relic in the age of Zoomer humour and infinite scrolling content, or potential for over-sentimentality - evaporated minutes into the film’s opening. The creative team behind Forever, the stewards of this franchise, knew that the film needed to be about friendship and connection, a masculine culture of dares and serotonin-chasing ever heightened by real physical stakes. It delivers in every stupid vignette, whether its an over-engineered flotation tank the team leverage as they attempt to finally light one of Steve-O’s farts underwater, or Johnny Knoxville taking a crushing hit from a bull. The almost manic cheer of excitement when a stunt goes to plan, the sense of genuine relief when Knoxville gives a thumbs-up from the back of an ambulance. The bonhomie shown by cast members old and new as they stack themselves face to face on the ground to create a human ramp for a BMX to trick off of.

As an audience we share in the pain, we applaud the successes. We laugh at and with the cast simultaneously. It’s an absolute joy. A series of incredible catharsis and release because it’s grounded in something so recognisably tangible and human.

But the game, launched 15 years prior at the height of Jackass-mania, fails on all of these fronts. Despite its aesthetic authenticity - mo-cap and voice work by the Jackass team, development suggestions from Knoxville and co - it’s cold and lifeless.

It’s a mini-game collection, because of course it is, with each stunt being converted into its own distinct little bit. Controls are left permanently on screen since the function of the ‘X’ button in one task is unlikely to perform the same action in the next.

The range of activities is reasonably varied, and tries to riff on some of the established iconography and mise en scene of the show and movies: shopping carts, bulls, excrement. But any of these things in isolation, again miss the point of why people watch Jackass. It’s in the interactions not the objects themselves.

In one particularly dumb mini-game, you compete against another cast member to ride a shopping cart across a roof top, seeing who can stop closest to a marker like curling or bowls. Penalty for failure though? Stop too short, and your character will express their disappointment through canned lines non-specific to the event. Stop too late? You fall off the building. Chris Pontius or Steve-O or Danger Ehren fall off a multi story building presumably to their death. Is that funny? Is that in the spirit of Jackass?

During one stunt in Forever, potential-interloper-but-actually-incredibly-affable Sean ‘Poopies’ McIrney takes a particularly harsh tumble that seems to render his body lifeless. The mood of the cast instantly drops as they rush to his aid and call for medical assistance. When he comes to, makes a quip, and then allows play to continue as the gang whoop and high five and holler: that’s the spirit of Jackass.

–

So what does it take to make a good tie-in game? A good adaptation? Here’s five examples of games of mixed quality, but that absolutely do their source material proud.

1. Enter the Matrix (2003) / Path of Neo (2005) (Shiny Entertainment)

A 2-for-1 to kick things off here. These are so, so action games. But they’re pretty fantastic The Matrix games.

The Matrix, after its first entry, became a franchise of intertextuality. Think how much stock was placed in series expansions like The Animatrix, or the basically canonised storylines of The Matrix Online.

Enter the Matrix was notable for telling side stories to the second film in the original trilogy, complete with exclusive cinema footage. If you were desperate for the entire story of that messy, often unsatisfying film, you needed to boot this thing up on your 6th gen console.

Criticised for not focusing on Neo’s story, developer Shiny went back to the drawing board with Path of Neo, retooling and recontextualising iconic scenes from the movies as videogame set pieces. A special nod has to go to the final battle and cutscene preceding, where The Wachowski’s address the player directly to acknowledge that the showdown and martyrdom of the final scene just wouldn’t work as a ‘final boss’ in a user controlled game, and so have opted to present something different. It’s meta, it breaks the fourth wall, and it’s incredibly on brand and on franchise.

2. Star Wars Episode 1: Racer (1999) (Lucasarts)

The critical feeling towards Episode 1 has remained pretty middling to poor, but most seem to agree that the scene where everyone goes zoom zoom in their little flying cars was pretty good, knock-about fun.

The tie-in to the main film itself was serviceable, a tread through the prequel’s story beats in the sort of third person action game we’d largely come to expect alongside most marquee cinematic releases, but it was LucasArts futuristic retooling of the kart racing formula that stood out as a better representation of what made Episode 1, for better or worse, what it was.

The branding also allowed it to overtake more established futuristic racing franchises like F-Zero, Wipeout and Extreme-G in terms of sales. Whilst it’s hard to argue that Racer is actually a better game than a tentpole release like F-Zero X for example, it captured so much of the excess of Episode 1’s most redemptive scene, it’s hard to argue its worth as a great tie-in.

3. Telltale’s The Walking Dead (2012-2018) (Telltale Games)

Telltale’s adventure game formula reached its final form in their adaptation of The Walking Dead comic series, and in turn, managed to absolutely nail the tone of Robert Kirkman’s bleak graphic series. Zombies weren’t suddenly reinvented by Kirkman and co, but the comics offered a refreshingly honest and human take on the horror sub-genre arguably kick-started by George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead back in 1968.

Opting to focus on the stories of characters adjacent to those in the graphic novels instead of the book’s established leads allowed Telltale a bit of space to use the rules of Kirkman’s dog eat dog world to spin their own yarns.

As Telltale moved away from the esoteric item puzzles of their earlier Lucasarts / SCUMM inspired point and click adventures, The Walking Dead really represented how a revised focus on characters, storytelling and tough moral choices could open the often fussy genre to way more people. Coupled with the black humour, adult themes and tough decisions its comic namesake was best known for, Telltale’s The Walking Dead is an excellent companion piece to the comics, and an infinitely better adaptation of the source than the TV series and its own spinoffs.

4. Alien Isolation (2014) (Creative Assembly)

Alien Isolation is as good an Alien sequel as 1986’s Aliens, and consequently better than every other piece of Alien-related media released since the mid-80s.

The original Alien is a masterclass in less-is-more horror. Set aboard a space vessel, the crew, penned in, make the sudden realisation that there is something unpredictable and dangerous on board. This set up manufactures a level of persistent dread that can be quite tough to stomach as an audience. A lot of quiet, with occasional violent crescendos.

And that’s the format of Alien Isolation. A proper survival horror game that has you shimmying through ducts as Ripley’s daughter Amanda, cobbling together makeshift weapons and tools, and being consistently shocked when that one xenomorph drops down to say hello when you least expect it.

Listen to us talk to the performance capture artist behind Amanda Ripley here.

5. Little Britain: The Video Game (2007) (Gamerholix / Gamesauce)

Little Britain is an incredible example of why traditional sketch shows have become increasingly redundant in modern comedy. A conveyor belt of half a dozen jokes, iterated on until the core laugh has been watered down so much that it almost becomes vapour. A punch line that becomes a catchphrase that becomes an annoyance. Stereotypes that attempt to do the comedy’s heavy lifting. Lazy, borderline offensive, criminally unfunny stuff.

It didn’t need a tie-in game. But in 2007, with the PS2’s shovelware era in rude health, any cultural artefact as ubiquitous as Little Britain was always going to get one.

It’s a hateful game based on a hateful show.

Terrible, repetitive one liners. Minigames that grow increasingly less enjoyable with each repeat. Mechanics based around ageing genre archetypes: collectathons, mazes, simple matching puzzles.

Vapid, barrel scraping nonsense. And so, an incredibly accurate portrayal of this unpleasant Lucas / Walliams vehicle.